What is congenital heart disease?

Congenital heart disease, is one of the most common types of birth defects. Every day, around 13 babies in the UK are diagnosed with congenital heart disease. It is not always known why some babies develop congenital heart defects, and no two heart defects are the same.

People with congenital heart disease will require life-long monitoring and treatment. Fortunately, as medical care and treatments have improved, people born with congenital heart defects are now living longer and healthier lives than ever before.

Our specialists are at the forefront of innovations in treatment for congenital heart disease and provide care from before birth and into adulthood across Evelina London Children’s Hospital and Royal Brompton Hospital.

What is congenital heart disease?

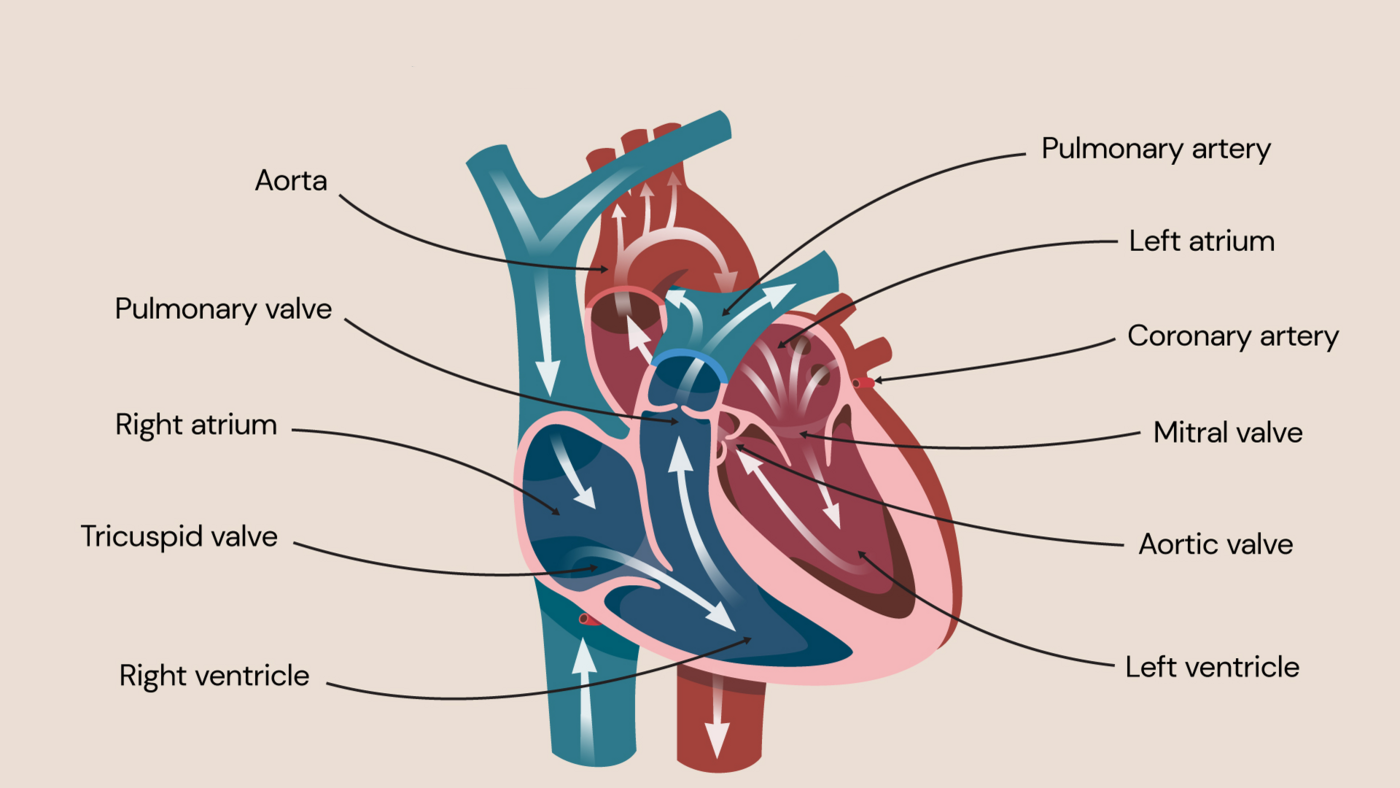

Congenital heart disease is a collective term for a range of birth defects that affect the heart walls, valves, and arteries and veins in the heart.

Congenital heart disease is a collective term for a range of birth defects that affect the heart. These include defects within:

- the heart walls

- the heart valves

- the arteries and veins near the heart

In congenital heart disease, blood flow can slow down, go in the wrong direction, or become completely blocked.

Many children with the condition do not require treatment, but others may need to undergo a range of treatments, including medication, surgery, and ongoing monitoring to track their health and progress into adulthood.

Types of congenital heart disease

There are lots of different types of birth defects and so there are also many kinds of congenital heart disease. Sometimes a person may have just one of these types, or they may occur in combination with one another.

Some of the most common types of congenital heart disease are:

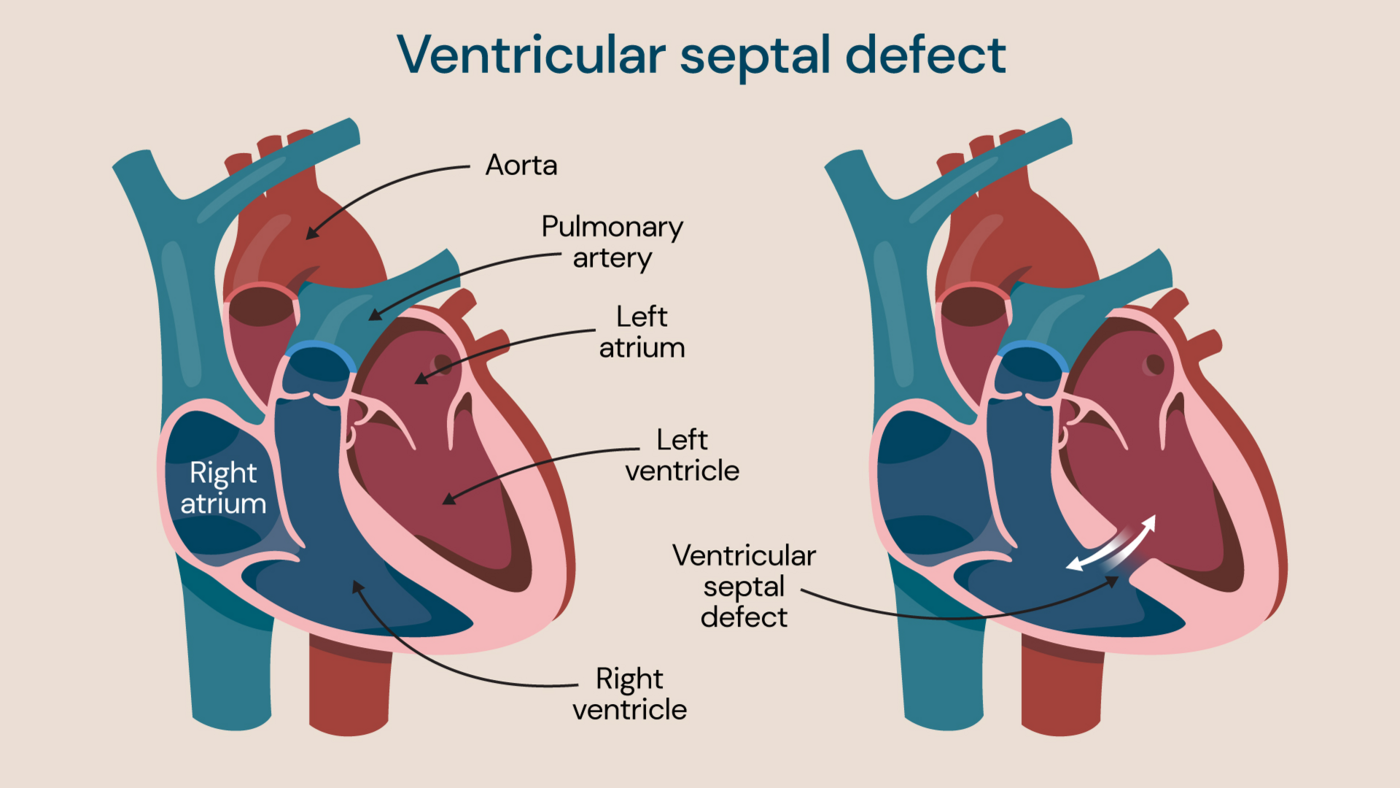

Septal defects

A septal defect occurs when a hole occurs between two chambers of the heart

Better known as a ‘hole in the heart,’ these occur when there is a hole between two chambers of the heart.

When this hole occurs between the top two chambers of the heart it is known as an atrial septal defect (ASD). If small enough, it may get smaller and close on its own as a child grows. Some however will need closing either by a keyhole technique (catheter Intervention) or open-heart surgery.

A hole that occurs between the bottom two chambers is known as a ventricular septal defect (VSD). Many of these will also close on their own, but again some may need open heart surgery. VSDs are the commonest type of congenital heart problem.

Narrow aorta

Also known as coarctation of the aorta, this is where the aorta — the main large artery in the body — is narrower than normal.

Pulmonary valve stenosis

This is where the pulmonary valve, which controls the flow of blood out of the lower right chamber of the heart to the lungs (where oxygen is put into the blood and carbon dioxide is removed), is narrower than normal. This restricts blood flow and makes the heart work harder than normal. It is the most common congenital heart valve defect.

Bicuspid aortic valve

The aortic valve sits at the exit of the left ventricle (chamber) and lead to the aorta controlling the flow of blood out of the heart to the rest of the body.

The valve usually has three flaps or leaflets that open and close to control blood flow, but in bicuspid aortic valve, there are only two flaps inside the valve.

This affects the way that the valve works, which can mean that the heart must work harder than usual, or that the valve leaks and allows blood to flow back into the heart.

Transposition of great arteries

This occurs when the aorta and the pulmonary artery have swapped position during development and come from the wrong ventricle.

Symptoms of congenital heart disease

The symptoms of congenital heart disease can often be detected at birth, although mild defects may result in symptoms only being noticed when a child is much older or when they are adults.

Some of the signs that a child may have a congenital heart defect include:

- rapid heartbeat

- rapid breathing

- extreme tiredness

- swelling of the abdomen, legs or around the eyes

- tiredness and rapid breathing in a baby

- a blue tinge to the skin or lips

Older patients with congenital heart disease may experience symptoms including:

- breathing problems

- dizziness

- abnormal heart rhythms

- fatigue

- fainting

- stroke

Symptoms of congenital heart disease vary according to the type of heart defect and the severity of the condition.

If any of these symptoms are noticed in your child or yourself, it’s crucial that you speak to a doctor.

Causes of congenital heart disease

Congenital heart disease is the result of a problem with the development of a baby while they are still in the womb. In most cases, it is not clear why some people develop heart defects and others do not.

However, there are some factors which are known to make a congenital heart defect more likely:

- having an infection, like rubella, while pregnant

- smoking or drinking alcohol during pregnancy

- having poorly controlled diabetes (either type 1 or type 2) while pregnant

- taking certain medications during pregnancy, including statins and some acne medications

Congenital heart defects are also more likely in people with Down’s syndrome, and in families where there is a history of children being born with chromosomal defects.

How is congenital heart disease diagnosed?

Ultrasound scanning during pregnancy means that many cases of congenital heart disease are diagnosed before a baby is even born. This is because ultrasound uses sound waves to produce images of your baby and your baby’s organs.

These scans make it possible to see the size and shape of your baby’s heart, and even watch it functioning. If there are concerns, a special type of ultrasound called fetal echocardiography may be carried out at between 14 and 22 weeks of pregnancy to determine the exact diagnosis.

Nevertheless, sometimes congenital heart defects are not detected on ultrasound, especially if they are only mild.

If there are concerns relating to heart function after birth, further diagnostic tests for heart conditions — including echocardiograms, chest x-rays and MRI scanning — may be performed to help make a diagnosis.

If heart concerns are suspected in young children, we offer a one-stop cardiology diagnostic service for patients at Evelina London Children’s Hospital and Royal Brompton Hospital. This service is designed to streamline the diagnostic journey and provide answers quickly. In a single appointment, our specialists aim to assess the child, perform and interpret tests, and provide a diagnosis with a plan for the next treatment steps.

If the scans performed during the appointment (echocardiogram and electrocardiogram) do not provide definitive results, our specialists may recommend a cardiac MRI or exercise test at an additional appointment to help build the bigger picture.

Treatment for congenital heart disease

Every case of congenital heart disease is different and so treatment plans are created for their individual needs.

What treatment looks like will mostly depend on the type of heart defect and how severe it is. Any other health conditions and how much a child weighs when they are born may also play a role in deciding which treatment is best for them.

Active monitoring and watchful waiting

Some heart defects, like some septal defects, resolve on their own. If they are not causing serious symptoms, then a consultant may choose to monitor a child as they grow and see if the defect heals.

Medications

Some medications can help to treat congenital heart disease. Exactly how they work will depend on the type of congenital heart disease.

Surgery for congenital heart disease

There are many different types of catheter procedures and surgery that can be used to correct congenital heart defects. These can include:

- a balloon valvuloplasty to widen a narrowed heart valve

- valve repair or valve replacement surgery

- surgery to close a septal defect (hole in the heart)

Surgery may be offered shortly after birth or later in life, depending on the type of congenital heart disease.

We also offer advanced surgical treatments for more complex congenital heart defects at our hospitals. These include the Norwood procedure for babies, and PEARS and Ross-PEARS for older patients with congenital heart disease.

Norwood procedure

The Norwood procedure is complex surgery with multiple steps. It is performed in newborn babies to correct a condition called hypoplastic left heart syndrome – when the left side of a baby’s heart doesn’t develop correctly, preventing blood from flowing as it should.

The operation enables a baby’s right ventricle to take over the role of the left ventricle which is underdeveloped and unable to push oxygenated blood around the body. After surgery, the right ventricle continues its role to pump blood to the lungs, but also to the rest of the body.

Personalised external aortic root support (PEARS)

PEARS is a revolutionary device, which has been around in clinical practice now 20 years since it was first pioneered at the Royal Brompton Hospital. It is used across both of our sites routinely to treat and manage heart problems in people with Marfan syndrome and other syndromes. Marfan syndrome — a genetic disorder of the connective tissue — can cause the wall of the aorta to weaken and widen.

PEARS is a custom-made treatment for the aorta that involves the creation of a medical-grade polymer mesh to support the aorta and prevent it from widening and rupturing.

Since everyone has a uniquely sized aorta, a computer-aided design is used to create a 3D printed model of a patient’s individual aorta based on a specific CT scan, which will be used to make their bespoke support.

Ross-PEARS combined procedure

Our specialists offer a new type of combined surgical procedure called Ross-PEARS for young and middle-aged adults with congenital aortic valve disease.

Traditional surgery to replace an aortic valve involves the use of an artificial valve. This can require patients to take blood-thinning medications for the rest of their lives and/or have repeat surgery a few years later, which is not ideal for young patients.

The Ross procedure uses the patient’s own healthy pulmonary valve to replace the faulty aortic valve. There are several medical benefits to this, including the elimination of the need for blood thinners and the valve not requiring replacement in future.

As low-pressure blood normally passes through the pulmonary valve, it may need additional support in its new position where blood flows through it under high pressure.

With the Ross-PEARS combined procedure, a PEARS mesh sleeve (see above) is added to support the pulmonary valve in its new position, avoiding future stretching and leaking of the valve and therefore repeat surgery in the future.

Locations

Diagnosis and treatment for congenital heart disease is available at the following locations:

Discover our congenital heart disease experts

Introducing our team of specialists with expertise in congenital heart disease. Whether it’s safeguarding heart health or implementing advanced interventions, our specialists are dedicated to delivering personalised care tailored just for you.