What is a pacemaker?

A pacemaker, also known as a cardiac pacing device, is a small electronic device implanted in your body to help treat slow or abnormal heart rhythms, and support your cardiac function by controlling your heart beat. There are several types of pacemakers that provide different functions to help treat a number of heart conditions.

What is a pacemaker used for?

A pacemaker can treat some arrhythmias or abnormal heart rhythms. Pacemakers can be programmed to work all of the time or just when needed. They work to regulate your heart rate if your heart beats too slowly or misses beats. Some special kinds of pacemakers can also synchronise the beating of your heart chambers and treat heart failure.

What does a pacemaker do?

“Your heart has a built-in pacemaker called the sinus node. It sends regular electrical impulses that make the top of your heart beat. These impulses then pass through the atrioventricular node which is like a junction box between the top and bottom of the heart,” explains our consultant cardiologist and electrophysiologist, Dr Wajid Hussain.

“This is the system which generates a normal heartbeat. If for any reason this system doesn’t work properly – i.e. the sinus node isn’t working correctly, an electronic pacemaker can take over this job.”

The device can replace the function of your atrioventricular (AV) node by coordinating the beating in the top of the heart to that in the bottom. It sends electrical impulses to make your heart contract, producing a heartbeat. The pacemaker doesn’t give your heart an electric shock; it sends electrical signals to the heart telling it to beat.

There are different types of pacemakers that work according to your heart’s needs. Most pacemakers work on-demand, sending out impulses only when your heart beats too slowly. Modern pacemakers have advanced functions so they can even know when you are exercising and respond by pacing at a faster rate.

A special kind of pacemaker called a biventricular or cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) pacemaker coordinates the heart’s pumping action and treats heart failure.

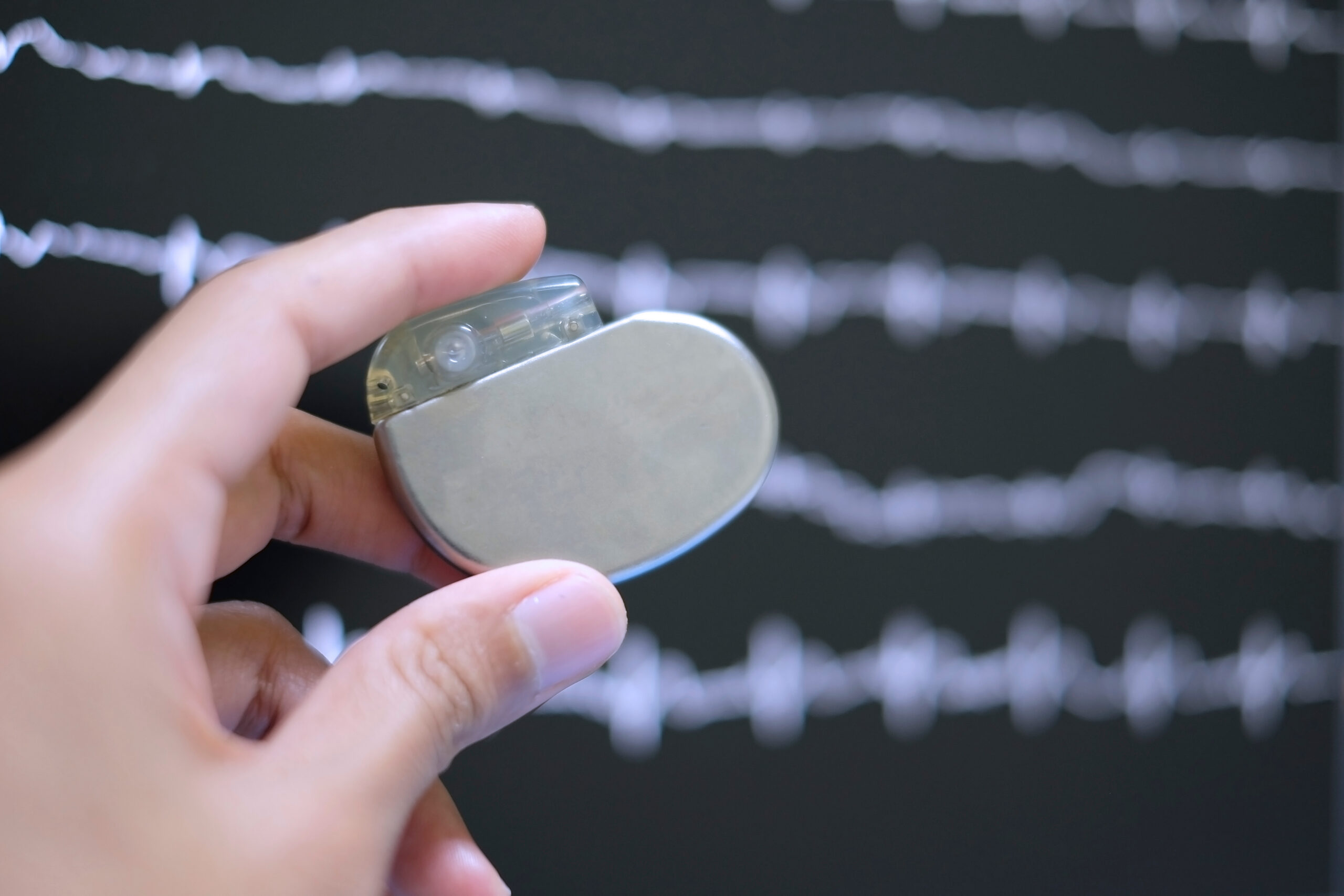

What does a pacemaker look like?

A pacemaker is a rectangular box, containing the chip which controls the pacemaker and the battery. Despite its complex circuitry it is usually smaller than a matchbox and weighs only 20-50 grams. The box is attached to up to three leads that thread through veins to different parts of your heart.

Modern pacemakers are tiny and slim. The tissue on your chest usually disguises it well, although you may notice a lump. Pacemakers are more evident if you’re very slim, in which case your doctor may place it under your chest muscle so that it is more discreet.

A pacemaker device

Where is a pacemaker located?

Most pacemakers are placed just under the skin beneath your left collar bone. Less commonly, your specialist may place it under your chest muscle, under your breast or under your arm.

Types of pacemaker

There are a few different types of pacemaker. The kind you’ll need will depend on your heart problem:

- Single chamber pacemaker: These devices have only one lead connected to either the right upper (atrium) or lower heart chamber (ventricle)

- Dual-chamber pacemaker: These pacemakers have two wires one of each connected to the right upper and lower heart chambers

- Biventricular pacemaker: Also known as cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) pacemakers, these have three wires connected to the right atrium, right ventricle and also the surface of the left ventricle

- Leadless pacemaker: Innovative pacemakers that are around a tenth of the size of conventional devices. They don’t have leads, are implanted directly into the heart and can have up to 9 to 13 years of battery life

What are the signs you need a pacemaker?

You may need a pacemaker if there are problems with your heart’s electrical conduction system or rhythm. Contact your GP if you are worried about symptoms including:

- fainting or nearly fainting – known medically as syncope

- your pulse is slower than usual all or part of the time

- frequently feeling faint or light-headed

- fatigue that affects your ability to do things normally

- shortness of breath

- chest pain

- palpitations – a pounding or fluttering heartbeat

- heart rate pausing or skipping a beat

- ankle, leg or abdominal swelling due to fluid collecting

Why do I need a pacemaker?

You will need a pacemaker if there are problems with your heart’s electrical conduction system or pumping function:

- Bradycardia: The most common reason for having a pacemaker is your heart beating too slowly. Your heart can beat too slowly because there’s a problem with your heart’s electrical conduction system. A pacemaker can speed up your heart all of the time or when it falls below a specific rate so that it beats at a regular rate

- Heart failure: If your heart isn’t working as well as it needs to, a cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) pacemaker can help coordinate its pumping action and improve its function

- Sick sinus syndrome: A group of different conditions in which your heart’s natural pacemaker doesn’t work properly. Your heart rate may go too fast, too slow, pause for short times, or may alternately go too quickly and then slowly

- Heart block: A problem with an electrical node in your heart that connects the top and bottom chambers. It can delay or stop the electrical impulses between the chambers and slow down the heartbeat. Heart block can develop as a result of ageing, heart disease due to certain drugs, and rarely people are born with a type of heart block

- Atrial fibrillation: Atrial fibrillation or AF is an abnormal heart rhythm that develops in the top chambers of your heart. The heart beats irregularly. If it is too slow, a pacemaker can help; medication is often used instead if it is too fast

- Cardioinhibitory syncope: You may faint or collapse because of a pause in the heart’s rhythm

How is a pacemaker fitted?

A pacemaker is fitted by pacemaker surgery. Pacemaker implantation is a minimally invasive surgical procedure carried out in a cardiac catheter lab, commonly known as a ‘cath lab’.

The procedure is performed under local anaesthetic but in some cases, a general anaesthetic may be required. Pacemakers are usually fitted as a day case, meaning you won’t need to stay in the hospital overnight. However, your cardiology team may keep you in the hospital overnight or longer to closely monitor your recovery.

Types of pacemaker surgery

“When a pacemaker is fitted, you will usually have a local anaesthetic to numb the area and sedation to keep you relaxed and comfortable. You may feel some pushing and pulling, but the procedure shouldn’t be painful,” explains Dr Hussain.

There are two ways of fitting a pacemaker. Your cardiologist will recommend the best technique in your case:

Transvenous pacemaker surgery

Most people have transvenous or endocardial pacemaker implantation. Your cardiologist will carefully clean and sterilise the insertion area and give you antibiotics to prevent infection. They will make a small cut in the skin under your left collarbone. One or more fine leads will be inserted into a blood vessel in the area, then thread them through the vessel into your heart.

When the leads are placed, an X-ray will be carried out to confirm that the leads are in the correct position and connect them to the pacemaker box. The cardiologist will check the pacemaker is working and adjust the settings to ensure it provides the appropriate stimulation for your heart.

Your cardiologist will make a ‘pocket’ under the skin on your chest below your collarbone and insert the pacemaker box. Finally, they will use stitches or medical glue to close the incision and apply a dressing.

Epicardial pacemaker surgery

If a surgeon inserts a pacemaker during heart surgery or has difficulties inserting the leads through your veins, you may have epicardial pacemaker implantation. Your cardiac surgeon will insert the leads directly through the outer surface of your heart. They will usually place the pacemaker box under the skin on your abdomen.

How long is pacemaker surgery?

“On average, pacemaker surgery takes around an hour, but it can take a little longer, particularly if you need a biventricular pacemaker,” says Dr Hussain.

Pacemaker side-effects

The risk of side-effects and complications following pacemaker surgery is low, affecting one in 100 people after standard pacemaker insertion.

- Thrombosis: There’s a risk of developing blood clots in a vein in the arm on the side of your pacemaker. Clots can cause pain and swelling in the arm. Small clots can settle spontaneously; larger ones may need anticoagulant medication to thin your bloo

- infection: Infections usually develop within a year of surgery but can occur many years later. You may notice redness and swelling around the pacemaker and develop a fever. Contact your cardiology team, GP or NHS 111. Urgent treatment is needed to prevent the infection from spreading to the heart lining, lungs or blood, causing sepsis. Removing the pacemaker, treating the infection with antibiotics, and inserting a new pacemaker can often resolve the problem

- air leak: Uncommonly, during surgery, the needle used to insert the pacemaker wires into the veins can nick the lung, causing a collapsed lung or pneumothorax. These usually settle without treatment, but your doctor may use a needle or chest drain to treat a large leak

- pacemaker problems: Your pacemaker may malfunction if a lead is out of position, the battery fails, or an electromagnetic field interferes with the device. If your pacemaker malfunctions, you may experience hiccups, fainting or dizziness – so seek emergency medical support if you develop symptoms of pacemaker failure

- twiddler’s syndrome: Some people stroke, touch, and move their pacemakers, often without realising they are doing it. This sort of ‘twiddling’ can displace the pacemaker in the pocket